Master's Thesis

My computer science master’s thesis, “Towards an Unsupervised Bayesian Network Pipeline for Explainable Prediction, Decision Making and Discovery” is now available online here. Check out these reviews!

“I laughed, I cried…I’ll never forget that discussion of discretization options…” - The AI Daily

“The natural successor to the Robocop franchise…this thesis is a tour de force.” - Better Statistics and Gardens

Ok ok, jokes aside, this page is here to give you the short version of a thesis with a lot of content. I was told, and I felt it as I was developing the document, that the thesis was almost at the level of a dissertation; I am confident that with some more time, I could have developed it into one. Who knows, I may yet do so! I am just happy I can say that after the whole experience I was only more intrigued in what I researched, and not tired of the domains I covered. For consistency, my summary here will follow the structure of the thesis itself.

Also, hereafter I will use the acronym BN for Bayesian network, as otherwise you’ll be squawking “Bayesian” for the rest of the day like a parrot (trust me).

Contributions, Goals and Related Work

My thesis puts forward four major contributions:

- A “pipeline” known as “Unsupervised Learning under Uncertainty (U2)” for preparing data and learning BNs for enabling prediction, decision making and discovery in the face of difficult scenarios and limited data

- An exploration of existing discretization methods, proposal of new methods and a novel (to my knowledge) evaluation of one of these methods against other options, considering impact on BN structure learning

- Evaluation and application of the U2 pipeline, particularly and novelly applied to the task of predicting and preventing preterm birth utilizing the Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-be (nuMoM2b) dataset

- A user-friendly GUI, known as Bayesian Network Inspector, for inspection of and inference with BNs learned following this pipeline

First, as the above suggests, this thesis entailed a great amount of practical

implementation and coding work, not just research.

To give you an idea, almost each of the steps in the pipeline required a

separate script, encompassing data visualization and preparation, the

steps of learning, visualizing and predicting with Bayesian networks, and

some parallel programming for search.

This is to say nothing of the considerable experiments on discretization,

the implementation of my extension of “clustering-based discretization”, and

the creation of Bayesian Network Inspector with R Shiny.

For reference, I did almost all of my work for this thesis in R, about

which I knew very little when I started, but came to love.

(Using R in my terminal was sufficient for much of my work, but RStudio

became invaluable for setting up extensive discretization experiments.)

This decision was primarily motivated by extensive support for Bayesian network

learning, namely via the excellent bnlearn package, around which much of

my work was based.

Full transparency: my body of code developed for the Distributed AI Research (DAIR) lab at Hunter College and for this thesis is currently private.

Second, why did I work on these contributions? In my time working on the nuMoM2b data in the DAIR lab, I came to understand that for the challenge of predicting and preventing preterm birth there are four goals that need to be met. These likely hold for any machine learning project, but whereas for the medical context all four are critical, each may take on different weight depending on the project. These are:

- Prediction - here, predicting if preterm birth or another adverse pregnancy outcome might occur

- Decision making - deciding which tests or treatments might be helpful or optimal for a given pregnancy

- Discovery - while it is important to refer to existing medical knowledge, doctors have hope that machine learning will uncover new patterns

- Transparency and explainability - modelers, doctors and patients alike must be able to understand how we arrived at a certain model and the predictions and decisions it supports; this is also critical in avoiding issues of bias

The related literature section discusses some approaches that might be used to

meet these goals, and some advantages and disadvantages of each.

Supervised learning and reinforcement learning offer great power for

prediction and decision making, respectively.

Causal reasoning and discovery (learning causal relationships from data)

offer, in theory, the ideal solution to all four goals mentioned above.

However, when it comes to real world data like the nuMoM2b dataset, we

encounter issues which can stymie all of these methods to different degrees.

In particular, mixed data types, minimal and noisy data, insufficient temporal

granularity, missingness and outcome uncertainty (i.e. we cannot trust labels

such as preterm/term birth because of gestational age estimates), are all

problematic and only made more difficult given that preterm birth and

other adverse pregnancy outcomes are not well understood.

In this context, working within the realm of probabilistic modeling,

using only discrete (by that I mean nominal categorical) data to learn Bayesian

networks in an unsupervised approach, offers a method to meet all four of the

above goals in highly desirable fashion.

Background

Remember when I promised to keep this short? Well if I go into detail as I did in the Background section, then we’ll be here for quite a while, so let’s just establish a couple of basics.

- A BN is a pair of a directed acyclic graph (DAG, for short) - its “structure” - and a set of parameters. It can be specified manually, learned (typically in unsupervised fashion) from data, or something in-between. In general a BN is a generative model - one that doesn’t just tell you P(Y|X), the probability of some target given input features, but P(Y|X)P(X), i.e. how all variables in your data relate. In fact, BNs are great for when you have more than one target (i.e. more than one Y), such as when you want to predict a quantity or quality at multiple timepoints, given different amounts of information available.

- Handling mixed data types, temporal processes, missing data, and learning BNs from data are all active and exciting fields of research.

- To avoid making prohibitive distribution assumptions and to permit more flexible and intuitive models, one can convert all data to discrete form using a modeling step known as discretization, and then learn discrete BNs.

Unsupervised Learning under Uncertainty (U2)

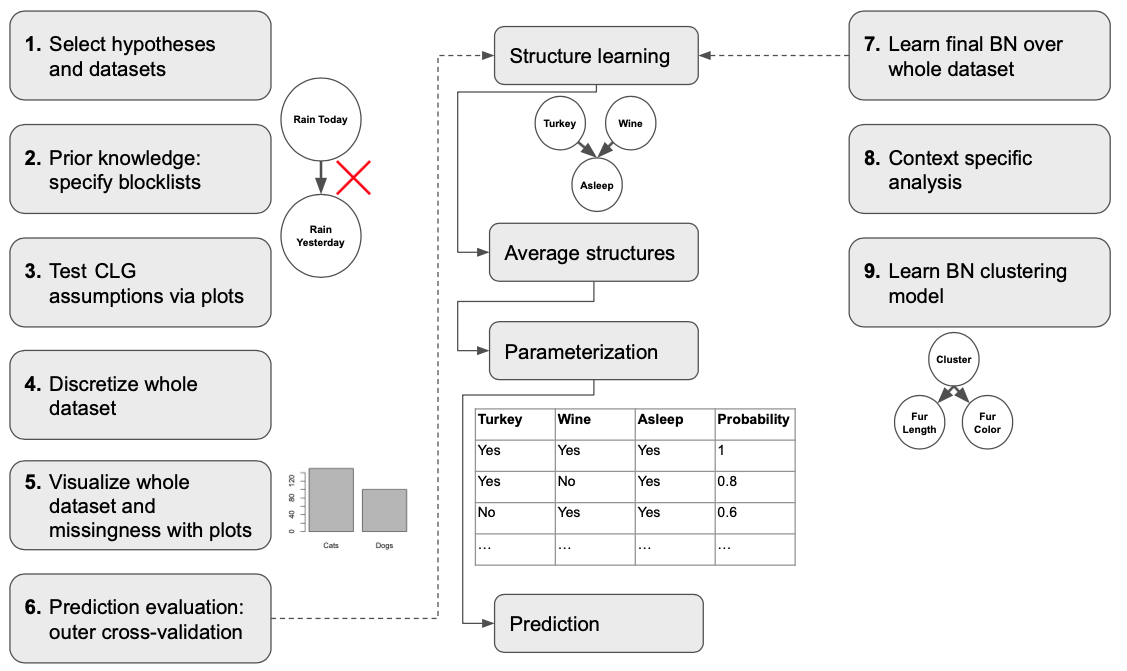

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then let’s save you some reading;

below is the process I proposed, pulling together everything I came to

understand about BN modeling and meeting the goals I laid out above.

As you can see the process starts with preparing your hypotheses and appropriate datasets, specifying the flow of time in the data so as to achieve models that are closer to causal representations, testing an alternative representation known as a conditional linear Gaussian (CLG) BN, and then discretizing, and visualizing your data. This is followed by BN learning, where we first evaluate our learning process in an outer cross-validation (i.e. multiple train-test splits), and then learn over the entire dataset; step 9 also features learning over the entire dataset, but here we learn a clustering model that offers additional insight into the data and as a sort of check on the discretization process (i.e. has our modeling obscured patterns we know should be present).

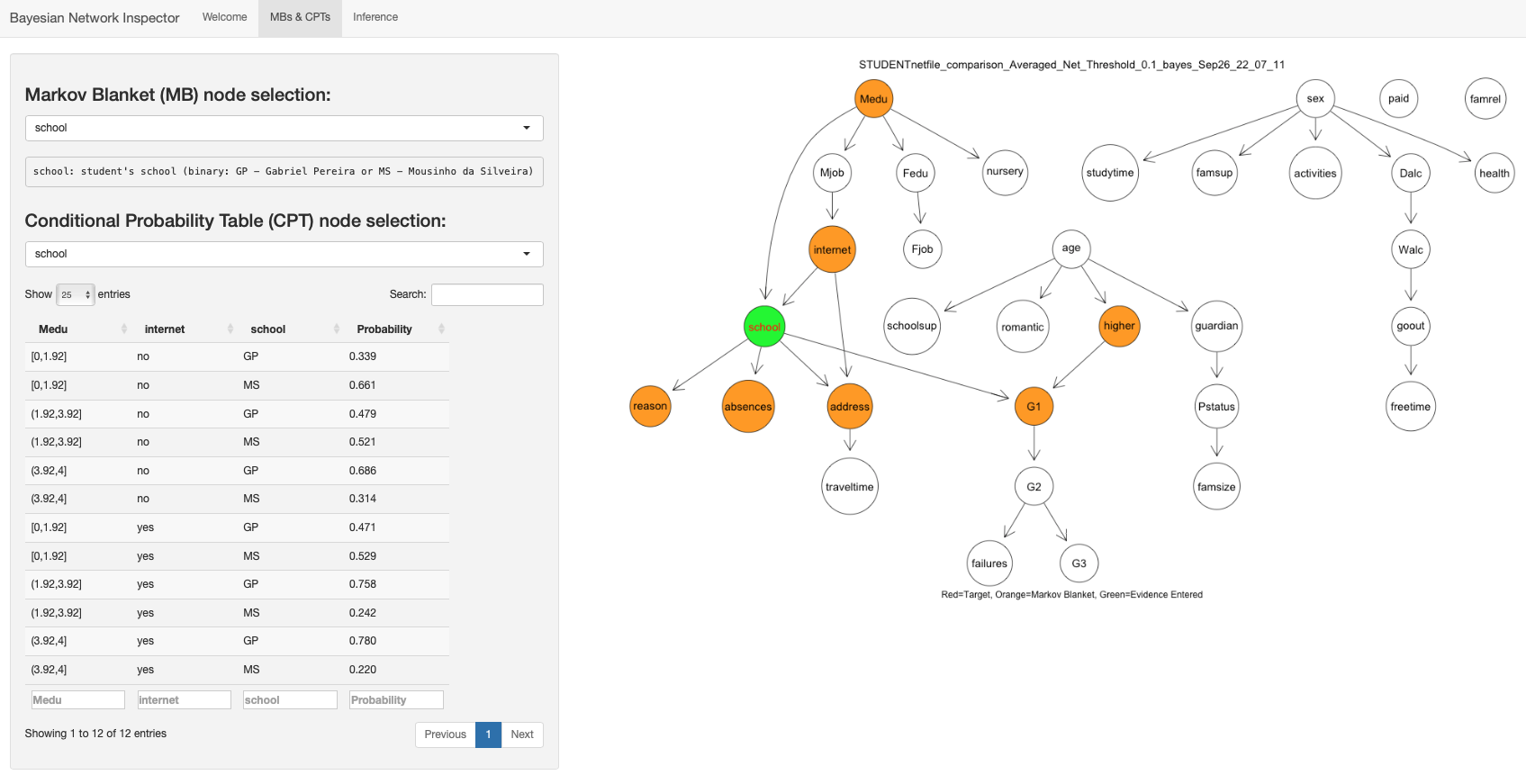

Also, here is a sample of the BN Inspector program I wrote to aid in

this work:

Discretization

Discretization, the process of turning continuous variables into discrete variables, such as blood pressure being converted into a binary high/low phenomenon, tends to get lumped into the “preprocessing” category, and as such it doesn’t get a lot of attention. (As mentioned above, it can be quite helpful for BN learning as it allows us to learn simpler and more flexible models). Accordingly, when modelers need to use it, they may just reach for the method most familiar to them, such as interval binning. Yet, as it turns out there is a whole universe of methods which can be organized along a number of axes. Furthermore, in considering the advantages and risks of this step, it becomes undeniably clear that this is a fundamental modeling step in its own right: can you imagine hand-waving data collection for ML away as “preprocessing”?!

Ok, rant aside, beyond rendering a summary of available methods and adding my own distinction for how to categorize discretization methods, I put forward two algorithms: one a re-formulation of an existing approach which could allow for simpler usage, and one a continuation of what is known as “clustering-based discretization”. The latter is the algorithm in which I was more interested and thought would be the more likely to bear fruit, so I implemented it and put it to the test.

- The algorithm: to achieve unsupervised discretization, we can first cluster our mixed data (continuous and discrete), get “labels” in the form of cluster ids, and then pass them on to a supervised discretization algorithm to make our dataset completely discrete.

- The test: we can quantify the consequences of discretization (read as information loss) by examining how well a known BN graph (i.e. structure) is recovered by structure learning algorithms; to this we can add the complication of missing data. (Small note: I offered options for dealing with missing data, and for when supervised discretization algorithms “failed” to discretize a feature.)

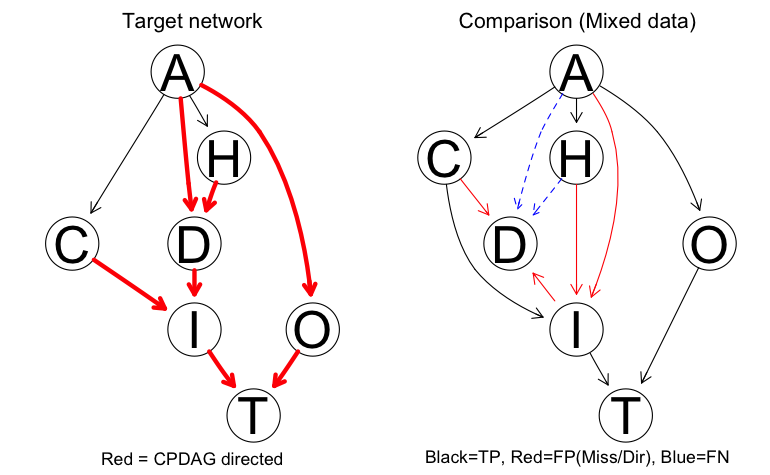

- The results: clustering-based discretization merited further investigation, and while discretization approaches risk loss of information, skipping this step didn’t offer any guarantee of perfect results (see below for all of the colorful edges showing learning failures when learning with mixed data).

Evaluation of U2

Studying preterm birth with the nuMoM2b dataset may have been a primary

motivation for my work but a fair evaluation of the proposed pipeline

called for more than testing on just nuMoM2b, a very difficult context.

Looking for another dataset with the same needs (prediction, decision

making, discovery and explainability) and some known performance

benchmarks, I worked on the

Student Performance dataset from the UCI repository.

This evaluation proved to be a success story, with prediction performance

comparable to supervised learning alternatives, and with discovery and

transparency that laid bare connections in the dataset that were only hinted

at by supervised methods.

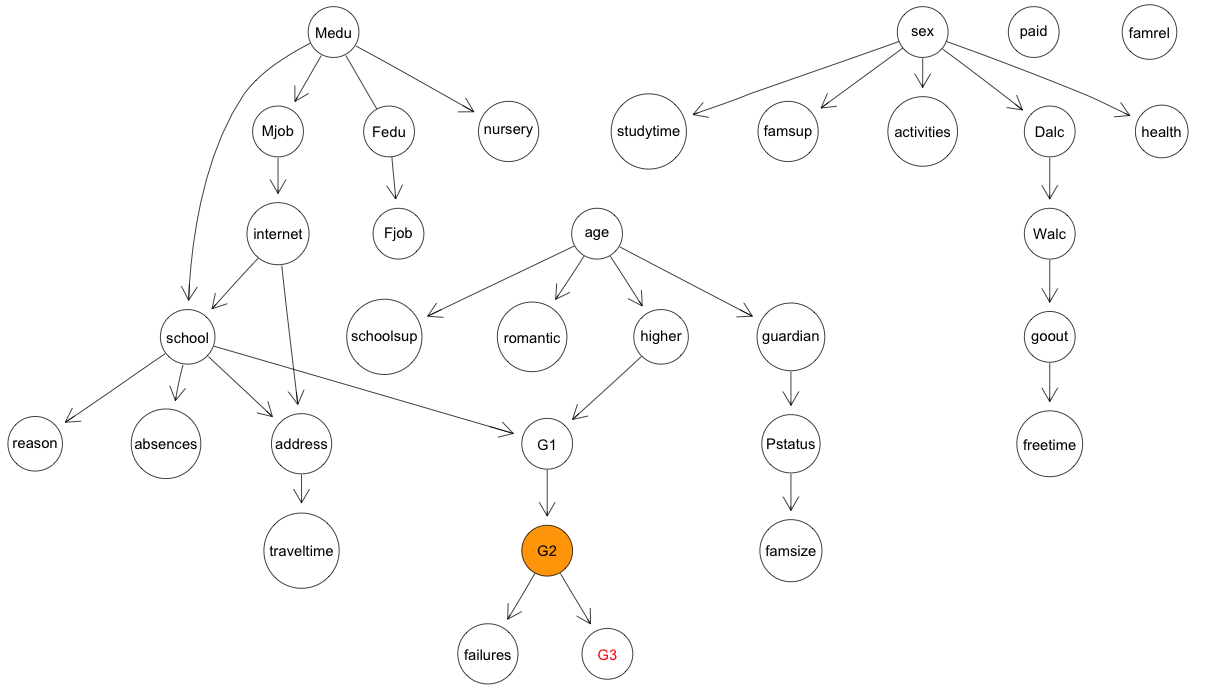

Below is the final structure learned over the entire dataset, which makes it

(unfortunately) quite clear that little directly related to the grades

students achieved:

Work on the nuMoM2b dataset was unfortunately limited by time; a couple of

weeks more would have permitted some additional experiments.

The preliminary evaluation proved to be something of a cautionary tale, as

the learned networks proved incapable of performing the prediction and

decision making support hoped for, but for what appeared to be as a

consequence of limited data.

Preparation of the subset of nuMoM2b data I used is a whole story in itself,

but suffice to say that the learned BN was still a success as a discovery

and transparency mechanism, highlighting the limitations of what could be

realistically learned with too few cases of treatment or adverse conditions.

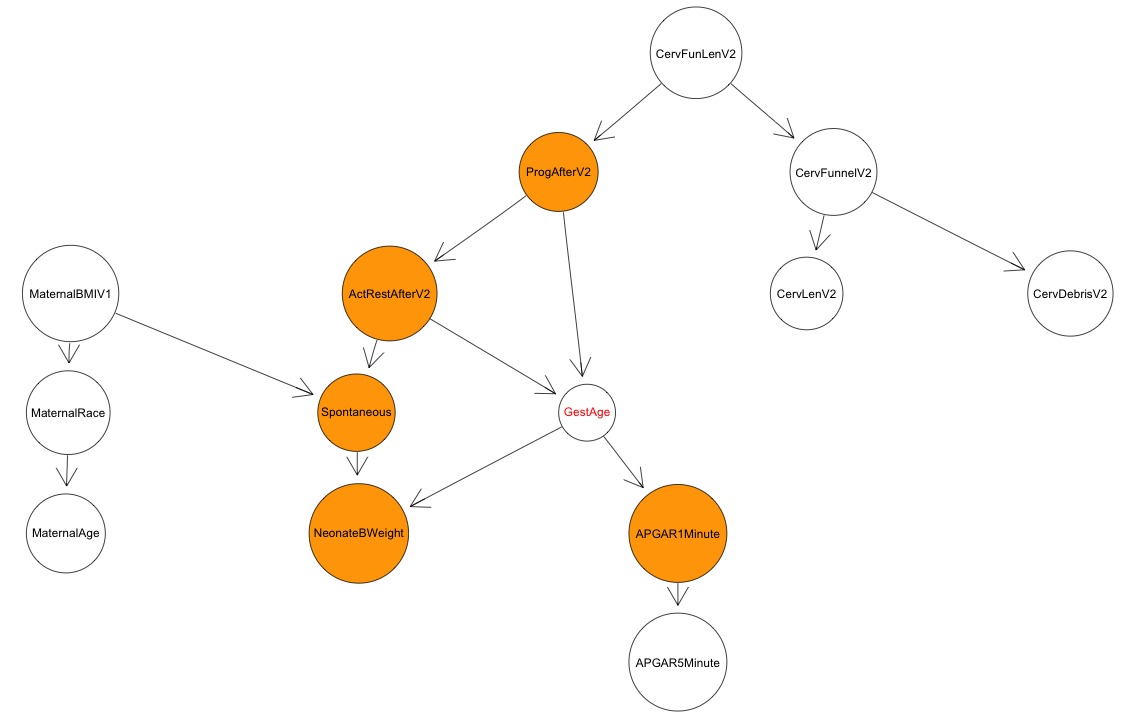

For reference, here is the final structure learned over the subset of data

I focused on relating to cervical conditions mid-way through the pregnancy

and subsequent treatments:

Takeaways

Thanks for sticking with me to the end! Don’t forget to comment, like and… I mean, I hope you got a little insight into what my thesis focused on.

BNs are a fascinating field of study with a very rich body of literature, and I think they have great potential to be the explainable AI needed in healthcare, but more research and extensive evaluation is required. The same need for more development is present for discretization, which can enable learning of simple BN models. The U2 pipeline, pipeline applications (Student Performance and nuMoM2b), BN Inspector, and discretization algorithms and evaluations I put forward in my thesis are my own humble contributions to this progress. My greatest regret with my thesis is that I did not have time to conduct even more experiments, but if you examine my document, you’ll see how much space is required just to unpack a couple of good experiments.